In the ever-complicating terrain of enterprise data architecture, where platforms multiply, pipelines get ever tangled, and abstractions unfold like labyrinths in an M.C. Escher's drawing, Bruno Freitag stands out for one reason: clarity.

As the author of Data Mesh Design: A Practical Pipeline Design Guide, Bruno doesn’t just theorize about data mesh. He builds it modularly, efficiently, and with an almost stubborn sense of pragmatism.

His work traverses regulated sectors and multi-domain organizations. Yet, whether the setting is an agri-supply chain or financial conglomerate, his core message stays constant: most companies don’t have a tooling problem; they have a technique problem.

In the Summer of 2025, we had the pleasure of having Bruno elaborate on design discipline, semantic nuance, Terraform fatigue, and the data-cultural traps that still threaten even the best-laid mesh plans.

"Too many enterprises confuse technique with technology," Bruno tells us.

And in his view, this is where most mesh initiatives lose their footing. The belief that a new tool or vendor can fix foundational misalignments leads to platform churn but not progress.

Instead, Bruno urges companies to ask deeper questions: Are we capturing the business meaning of our data, or just fulfilling technology?

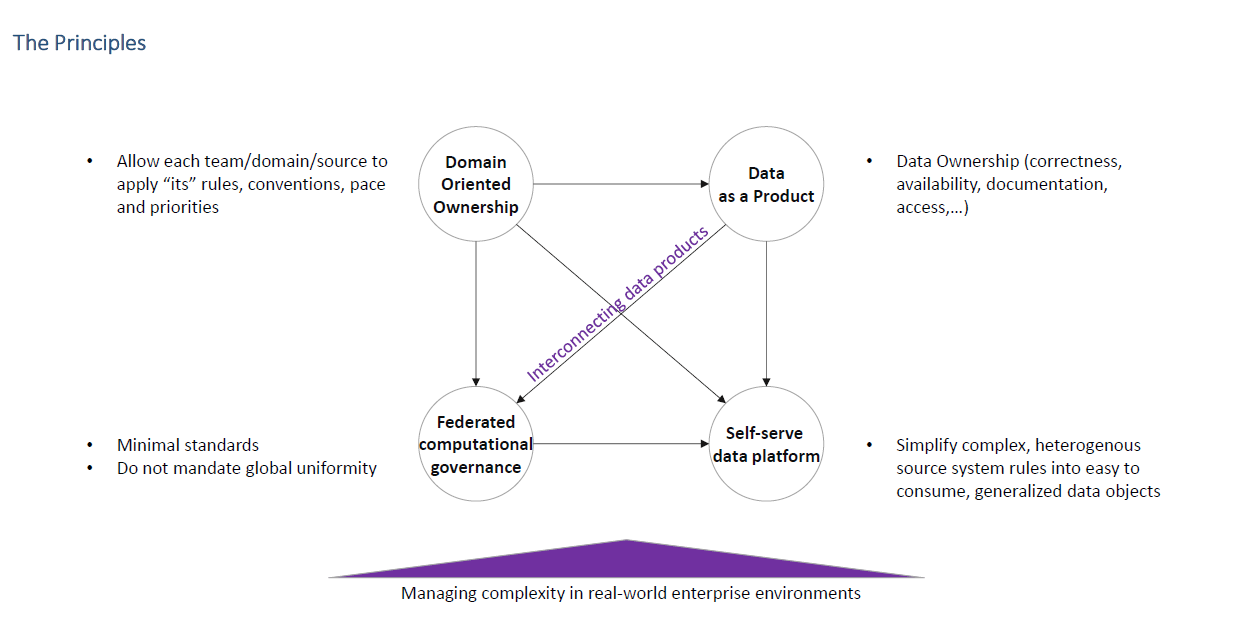

His design principles lean toward radical simplicity: build modular, linear-scaling systems with just enough governance and relentless semantic clarity.

In his own words:

"It’s not about creating more tooling. It’s about rejecting complexity-for-complexity’s-sake."

Bruno has little patience for overengineered platforms that become ends in themselves. He believes that the real differentiator lies in the team's shared understanding of core business concepts and their disciplined reuse.

Simply put, if you don't know how to box, no gloves on Earth will help you.

While mesh theater has drained budgets elsewhere, Bruno points to a radically different tempo.

“Value can be delivered in days,” he claims.

He recounts early mesh setups that merged agricultural sensor data, NDVI satellite signals, seasonal forecasts, and R&D metadata into an operationally meaningful nucleus.

The trick? Small, federated ownership of composable data objects.

The platform was Redshift, the logic was SQL, the orchestration was minimal. The outcome was tangible, cross-functional value.

These blueprints weren’t born in a lab. They were extracted from direct engagements. Sometimes it all can start with a single data join that enables an AI model to improve forecasting by 3%. And that’s the snowball.

What’s key, he emphasizes, is not size, but semantic integrity. The initial nucleus of a mesh doesn't need to cover the whole enterprise. It just needs to be real, relevant, and built for re-use and scale.

Much of Bruno’s book focuses on dynamic hierarchies, flexible identifiers, and multi-grain facts. These aren’t just modeling conveniences; they’re foundational to analytical resilience in the real world.

In his experience, some of the most deceptively simple data elements prove to be essential, yet they are overlooked.

Why? “Commodity” reference objects, like country codes, customer segments or currency definitions, are seen as negligibly small and taken for granted. Yet they often are the glue for building interoperable systems, especially as their codes and definitions vary across systems and functions.

Because they don’t clearly belong to any domain, they’re neglected, inconsistent, or worse, duplicated with slight variations and hence incompatible.

Bruno’s design framework explicitly accounts for these shared elements without forcing undue standardization:

“The blueprints describe a pattern for implementing even those like any others.”

Dynamic hierarchies, especially in sales and marketing contexts, allow organizations to reshape their go-to-market models without breaking time-series comparability.

Likewise, synonym mapping acknowledges the semantic entropy of large orgs:

"It’s fine for each domain to use their identifiers. Just ensure there's a place where mappings converge."

This modular design ethos, what Bruno calls the LEGO effect, allows teams to progress independently & combine components across use cases without creating semantic drift.

But it’s not magic. It requires discipline in how objects are defined, extended, and versioned. Bruno advocates for early – and collaborative! – reviews and principled reuse over re-invention.

And if you build a fact table at its finest granularity, you can derive many layers from it. No need to rebuild. Just extend.

Bruno cuts through buzzwords. For him, a lakehouse is just another "data pot", while the mesh is the organizational overlay.

"In practice, you need both. A mesh without a consistent data pot becomes brittle. A lakehouse without federated design becomes a centralized legacy."

His preferred stack varies, but the pattern remains: one shared platform, many distributed and independent teams.

Data movement is minimized, not glorified. And warehouse logic? Written in plain SQL, avoiding being locked in and readable by anyone who can reason about data.

What about provisioning? Bruno is a bit skeptical of high-abstraction DSLs. Automation is good, but more levels of abstraction or complex tooling in the data pipeline don't help agility.

“We experimented with them and they limited expressiveness and shrank our contributor pool. We reverted to SQL and streamlined orchestration. That’s what scaled."

Teams went through design reviews, sometimes 20 minutes with just Excel and sample data. Low-tech, high-impact.

Essentially, Bruno warns against the illusion that provisioning challenges can be “abstracted away” with clever wrappers.

Automate at will, but do it with clarity in data & with purpose. We all want repeatability, industrialization for creating fully automated data pipelines, not hand crafting each one.

Bruno is passionate about governance that enables rather than obstructs. His view is that good governance doesn’t require centralized CI/CD rituals or global backlog prioritization.

Instead, he proposes two steps:

These steps anchor domain autonomy without losing architectural coherence.

He’s also pragmatic about lineage and catalogs: automate wherever possible, but only track what matters.

And while he appreciates the ideal of data contracts, he admits that in enterprise life, they often fall to the altar of urgent delivery.

From a risk perspective, Bruno advocates for a federated accountability model:

“Let teams self-certify, but make the specification explicit. If they understand what business fact they're modeling, that’s the strongest validation you can get.”

A data mesh without cultural readiness is just entropy, Bruno warns. While he supports bottom-up prioritization, he insists on top-down vision. Leadership must define the direction, but let teams own the road.

Quick wins help, but political capital is the key.

"Perception is reality, facts are negotiable."

He notes that many business units resist mesh not because of complexity, but because they fear shared success and re-use means increased costs for them.

When should you not do mesh?

"If there's no drive to reuse data across functions, no desire to make the sum greater than the parts, don't force it."

Bruno’s approach to culture is refreshingly honest: start with evangelism, avoid mandates, and prioritize reuse over reinvention.

But don’t ignore the resistance:

“Data kingdoms are real. You don’t break them down, you make them irrelevant by offering something better.”

Despite writing the book on data mesh, Bruno doesn't treat it as a destination. It’s a means to a simpler, more transparent, more resilient data environment.

His final takeaway?

"If you focus on business facts, create clarity on semantic meaning, and let teams build with clarity, the architecture almost designs itself."

And it seems that’s where Bruno's recipe for success lies: not in louder frameworks, but in quieter foundations that make data mesh not just work – but scale and last.